The importance of compliance

My years of preparing for, and carrying out, ISM, ISPS and MLC audits, including the opportunity to advise companies on the review of their SMS, makes me well-qualified to assist you in any compliance management matter.

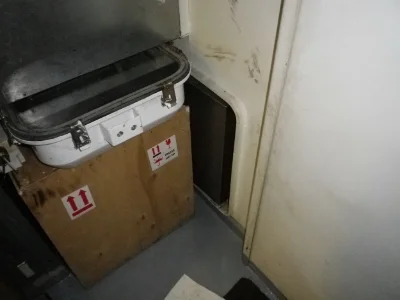

I can help you find some of the weak points in your physical on board safety arrangements and thereby assist that, for example, your cross-flooding ducts and/or emergency escapes are not blocked.

And, more to the point, I can offer you time which you and your employees/colleagues may not have, to review and develop a safety management approach which is fair and just and delivers the detailed reporting you require for your continuous improvement of your safety management system.

Compliance management

The ISM Code is the critical ship operations' framework for any seafarer and/or shipowner. The Code determines that compliance is not only required with statutory provisions but also with applicable codes, guidelines and standards recommended by the IMO, flag State, Class and other maritime industry organisations.

Compliance is not an end in itself nor is it just nice to have. Compliance will have a large impact on civil and criminal liability particularly for the company (and thereby, of course, their insurers), DPA and master (see also the reference to strict criminal liability under support). If the owner is a corporate body and not an individual person, master and company will be affected differently as a corporate body cannot be imprisoned.

Whereas company and insurers may only be the paymasters, the real master and the engineers may be taken out of service for some time if they, for example, tried to bypass the oil filtering system. The 2016 case of the GALLIA GRAECA in Seattle is a fitting example. In a second case, a German company had to pay a total of US$ 1.5 million.

Full compliance is usually hard to achieve and requires a sound safety management system operated by both company and seafarers with the right attitude. Apart from the necessary technical-nautical competency both on board and ashore a reporting system ought to be in place which allows comprehensive reporting of defects, incidents and accidents without recrimination. Open and fair treatment of those who make errors, be they skill-based, rule-based or knowledge-based would appear to be essential for a process of continuous improvement.

A good example of how reporting can be regulated to encourage employees appears to be EU Regulation 376/2014 for the aviation industry which is binding law in all EU countries. It clearly stipulates the sole objective of occurrence reporting to be the prevention of accidents and incidents and not to attribute blame.

The IMO Casualty Investigation Code does not as clearly address the same objective but still provides that it is not the objective of a marine safety investigation to determine liability, or apportion blame. This, however, is not addressed in one of the two mandatory parts of the Code but is a recommendation only.

Yet, in the context of near miss investigations in the company the IMO addresses in MSC-MEPC.7/Circ.7 that a distinction is drawn between acceptable and unacceptable behaviour. It is said to be a crucial requirement for a company to clearly define the circumstances in which it will guarantee a non-punitive outcome and confidentiality.

Introducing a just culture in the workplace, where gross negligence, wilful violations and destructive acts are not tolerated but where findings first lead to internal exchanges for improvement of safety conditions, may require a lot of discussions. This discourse should preferably involve all who are affected so that the right "buy-in" factor is achieved.

When I attended a bridge resource management course with Ravi Nijjer in Wellington in 2015, an Air New Zealand safety manager made a presentation. He told us that their approach to dealing with errors, of which apparently 2.5 occur on average on each flight, is set in three stages. First, console, secondly train if necessary, and thirdly discipline if no other option is available. When asked how many of their 1,700+ pilots where sacked during the last year he responded none.

If you want to read a bit more about this why not start with Sidney Dekker's Just Culture and/or Michael J. Sandel's Justice - What's the right thing to do?